NATIONAL ELECTION 2017

The data collected from the Elections Observation Group from the 2017 Kenya Elections shows that women as candidates were reported to experience violence more frequently than women as voters

On August 8, 2017, Kenya held its general elections, with President Uhuru Kenyatta being pronounced the winner by the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) on August 11, 2017, with 54 percent of votes. On September 1, Kenya’s Supreme Court nullified the August 8 elections and declared the results, invalid, null and void. The IEBC scheduled fresh elections for October 26, 2017 and on October 31, President Uhuru Kenyatta was re-declared the winner after securing more than 98 percent of the vote, after his main opposition opponent boycotted the repeat election.

Although the Kenyan Presidential election was contentious, the general results of the elections demonstrated an overall improvement in women’s political participation in Kenya. At least 23 women were elected to the National Assembly, up from the 16 elected in the last elections. Although the number of women who participated in the party primaries (11%) and in the general elections (7%) is still well below the constitutionally required not more than two thirds gender rule, there was a positive growth in the number of women aspirants, when compared to 2013.

Even with this improvement, the European Union’s Mission Observation concluded in its report that the Kenyan electoral process was damaged by political leaders attacking independent institutions and by a lack of dialogue between the two sides, with escalating disputes and violence, with the eventual result of the opposition withdrawing its presidential candidate and refusing to accept the legitimacy of the electoral process.

BEFORE THE ELECTION

During the pre-election period, Elections Observation Group (ELOG), a nonpartisan citizen election observer group, asked questions related to the upcoming general elections. NDI worked with ELOG to incorporate VAW-E specific framing and questions into their long term observer checklist and critical incident forms, including questions related to monitoring violence, and subsequently found that women were continuously a main target for threats and harassment. NDI worked with ELOG to gather supplemental information on perpetrators, victims, and specific manifestations of violence, specifically violence that particularly impacts women’s political participation in and around elections in the last three reporting periods. ELOG's data came from an observer in each of the 290 constituencies in Kenya, who reported in every two weeks using standardized checklists as mentioned above.

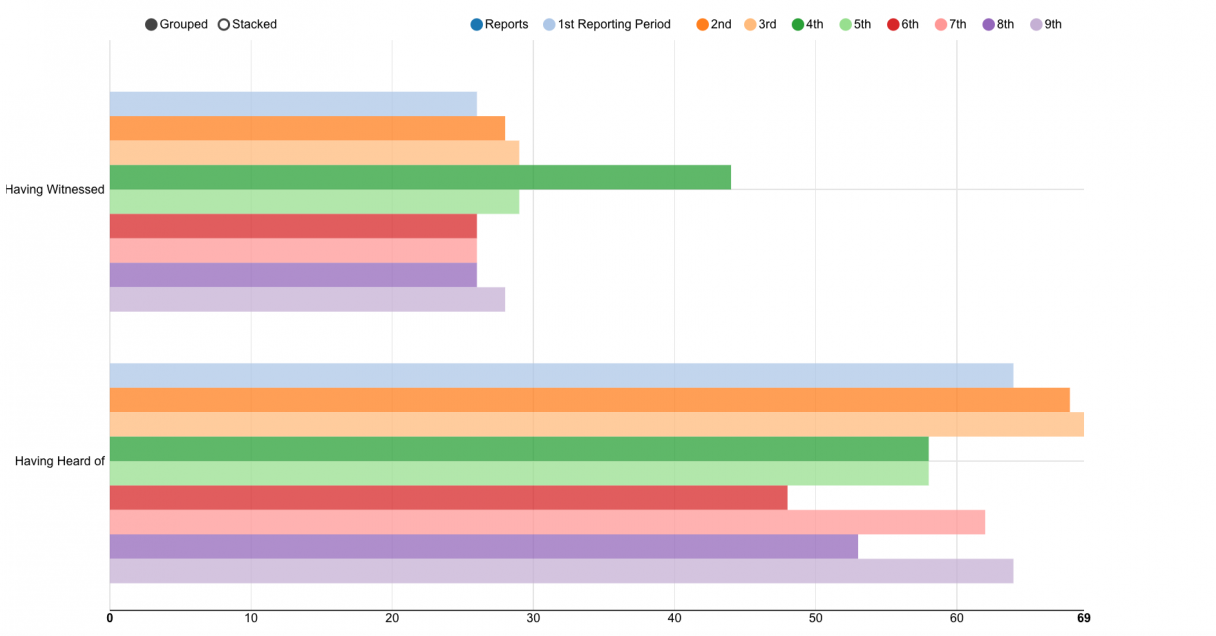

Through almost a 5-month reporting period before the general election, ELOG found that out of 3,157 responses, 972 responses (31 percent) answered that they had witnessed or heard of the use of threatening, abusive or insulting language against women as candidates or their families in their constituencies. There were significantly fewer reports of of the same question against women as voters or supporters, with only 597 of responses (19 percent) reporting this type of violence.

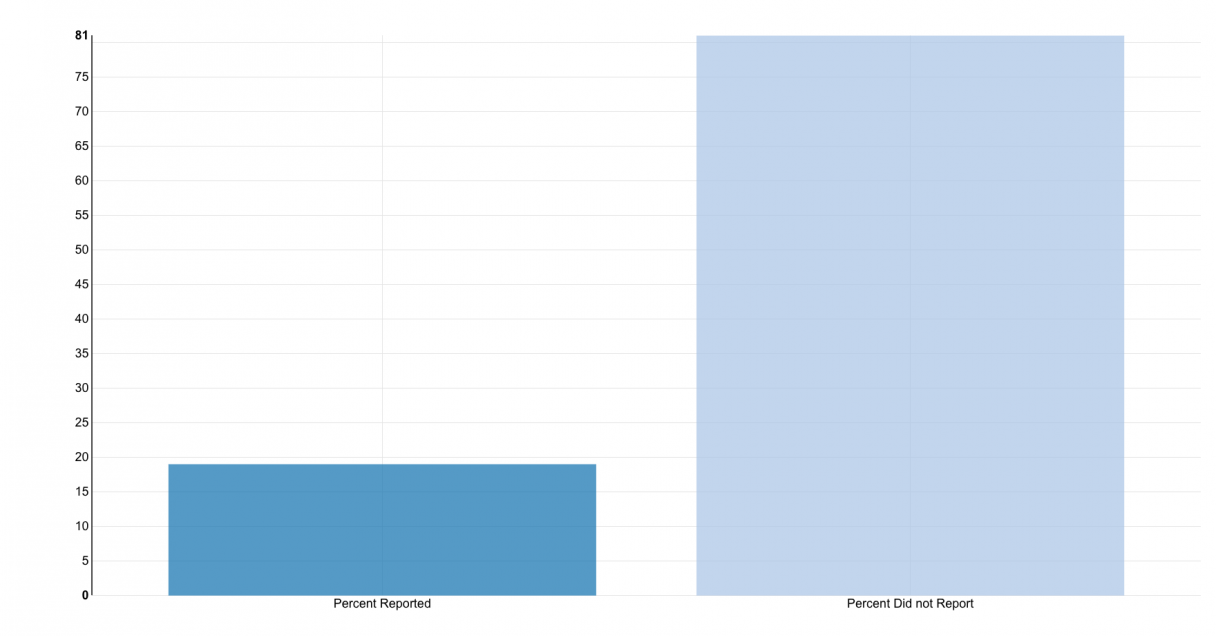

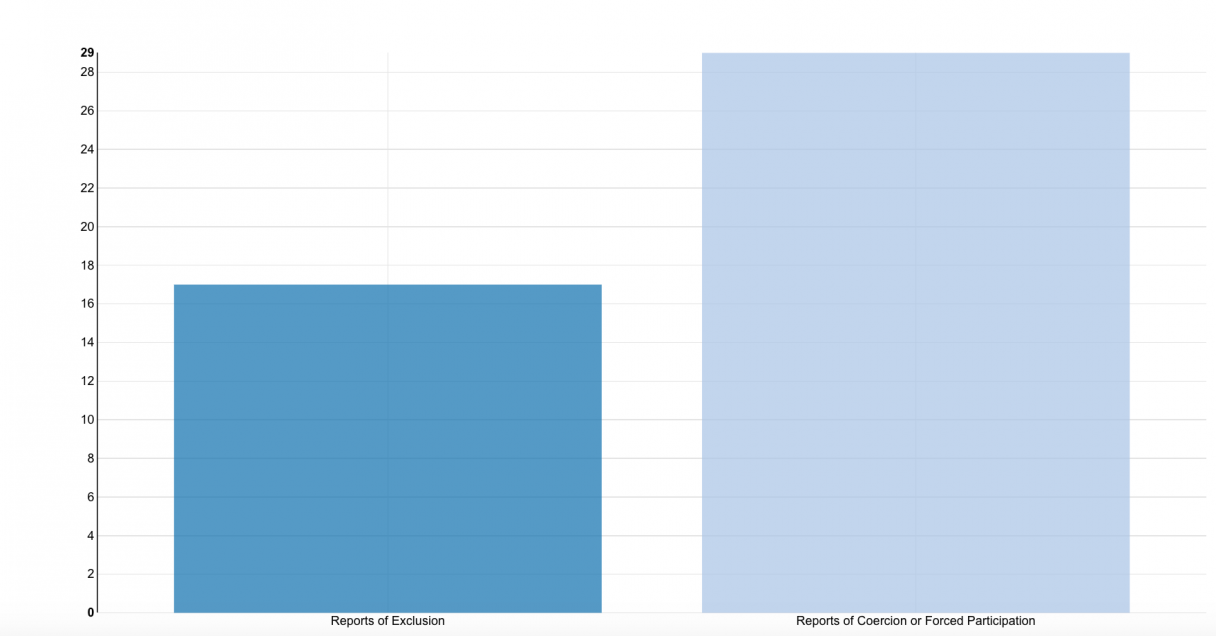

Over the last three reporting periods there were 867 reports submitted, with 25 responses (3 percent) of having witnessed or heard of physical violence against women candidates within their constituency and 13 responses (1.5 percent) for the same question against families or supporters of women candidates in their constituencies. There was also 30 responses (4 percent) of having witnessed or heard of the destruction of a woman candidates private property or campaign materials in their constituency. ELOG was also able to capture that there were 149 responses (17 percent) of having witnessed or heard of campaign activities or events where candidates, supporters or organizers having excluded women. There were even more at 250 responses (29 percent) of having witnessed or heard of incidents of candidates or party supporters being coerced or forced to participate in political events. For example, threatening them, or by giving or promising them money, food and/or gifts.

Percentage of Reports Who Witnesses or Heard of the Use of Threatening Abusive or Insulting Language Against Women as Candidates or Their Families

Percentage of Reports Who Witnessed or Heard of the Use of Threatening, Abusive or Insulting Language Against Women as Voters or Supporters

Percentage of Reports Who Witnessed or Heard of Any Campaign Activities or Events Where Candidates, Supporters or Organizers Have Excluded Women or Forced/Coerced Them to Participate

ELECTION DAY

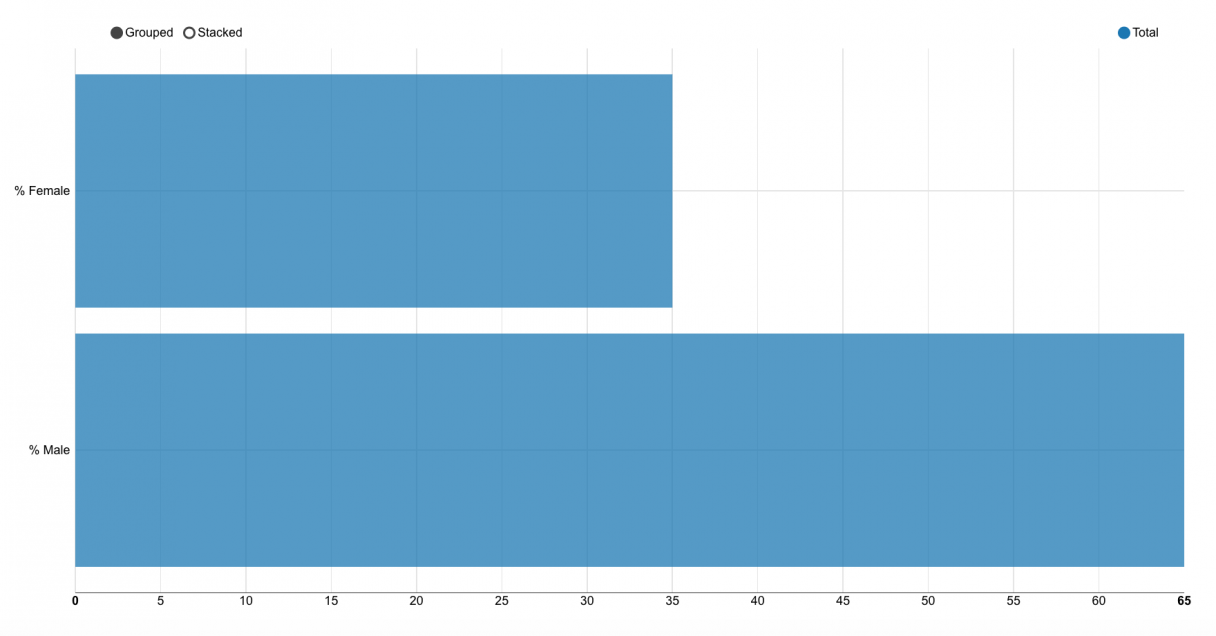

ELOG’s Parallel Vote Tabulation (PVT) data found that 35 percent of presiding officers in polling stations were women.

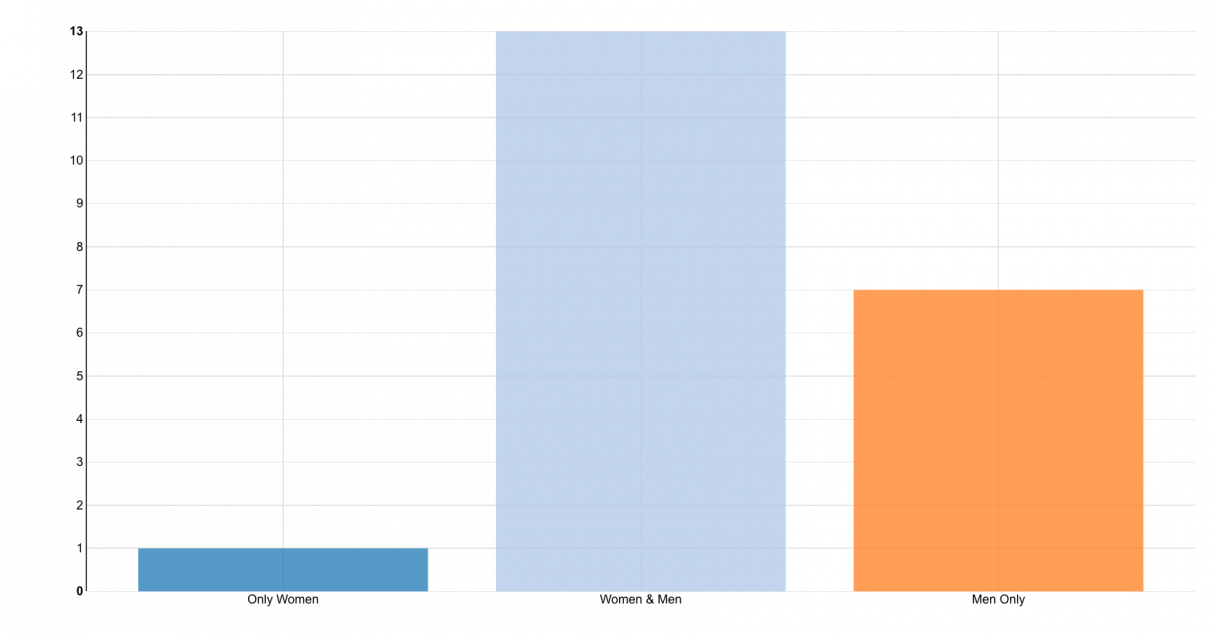

On election day, there was a low amount of incidents reported of violence to both ELOG and other observation missions. ELOG recorded 21 incidents of violence at polling stations. Of the incidents of violence, 1 involved only women and 13 involved women and men. The 1 female-only incident of violence was perpetrated against security personnel and the perpetrator was male and a voter, and the report of this instance was made after the observer saw it occur first hand.

Percentage of Female Presiding Officers in Polling Stations

Recorded Number of Critical Incidents of Violence

CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS

Since the 2013 elections, there has been little progress in improving women’s participation in Kenyan politics and mitigating the potential for election-related violence. The parliament has failed to promulgate laws implementing the country’s gender quota and has done little to prevent or mitigate violence against women. Women voters, candidates, and observers faced various forms of violence throughout the election cycle and examples can be found across the country. In the Northeast regions of Kenya, the concept of ‘negotiated democracy’ has meant that elders have worked across clan lines to establish seats that are specifically for their group. This power-sharing structure has meant that elders not only determine which seats are available, but also those who can compete for the positions. The opaque selection process has traditionally disadvantaged women candidates, some of whom have either been excluded from competing for seats or required to contribute to the community in order to be considered (a form of economic violence) or forced to run as independents if they wish to contest for office.

Women’s advocacy groups and the media reported numerous cases of women aspirants and candidates being harassed, attacked or discriminated against by other contestants and their supporters, or by their own party leadership. The European Union’s Election Observation Mission reported that in Trans Nzoia, two women candidates were threatened with sexual assault and in Mombasa a female Orange Democratic Movement (ODM) aspirant with a disability was repeatedly threatened with physical violence during the primaries. During the party primaries, Millie Odhiambo, not only had her house burnt down, but her bodyguard was run over and killed by a man driving an opposition campaign vehicle. In February, Eunice Wambui, an aspiring MP for Embakasi South, was attacked while on a voter registration drive in Mukuru Kwa Reuben, one of Nairobi’s sprawling slums. And in May, Esther Passaris, a Nairobi entrepreneur and politician running to be Nairobi County representative, was held hostage at the University of Nairobi by a group of male students. The students demanded that she give them 150,000 Kenyan shillings (US$ 1,500) before she managed to escape. She was at the university to address a women’s welfare association.

Women voters also were reported to have experienced the impact of violence during the electoral period. Mulika Uhalifu, an organisation that was working to highlight cases of electoral offences and insecurity in Nakuru County during the party primaries reported that women voters requested separate voting queues during the party primaries to avoid cases of indecent touching. Many women voters are also not at liberty to vote in their preferred candidates as their spouses control these decisions through control of their identification documents and assisted voting on the day.

On a broader scale, according to Human Rights Watch, Kenya’s recent election were marred by violence and serious human rights abuses, especially in opposition strongholds in Nairobi, Nyanza, western Kenya, and the Coast. The violence, documented in August included patterns of police use of excessive force against protestors, killings, beatings and maiming of individuals, looting and destruction of property. There were also attacks on civil society organizations and human rights defenders, journalists, judicial officials and suppression of freedom of expression. Both Human Rights Watch, the European Union’s Election Observation Mission and others also reported widespread accounts of sexual violence against women and girls, with allegations of rape, unwanted sexual touching, and beatings on their genitals, including by members of security forces and militia groups and civilians. The uncertain environment and fears of insecurity also reportedly resulted in more women than men temporarily moving back to rural home areas, and thereby jeopardising their possibility to vote.

All of these incidents and corresponding reports confirm that violence against women, whether as candidates or voters, occurred in a widespread manner.

ANALYZING ELOG’S DATA

ELOG’s data, while perhaps not as robust in accounts that were recorded by other groups, does demonstrate that violence against women as candidates and voters did occur within the Kenyan elections. Interestingly, ELOG’s data demonstrated that reports of violence were made more frequently for women as candidates than as voters. This could potentially evidence that women may be seen to be able to participate in politics, but experience greater backlash when they attempt to lead in politics. The fact that women were coerced into certain demonstrations of political participation more often than they were excluded reinforces the notion that the political participation of women is deemed appropriate generally, but only when it aligns with the limited expectations of a woman's family and/or community.

One more broader and interesting trend that ELOG was able to capture through its reports was that violence against women as candidates was reported more frequently in the primary election season. This is likely because most of the women candidates did not make the candidacy in the general election.

FOLLOW-UP NDI FOCUS GROUPS

Following the election, from September 26 to 29, the National Democratic Institute held four focus groups in Kenya in three counties: Kisumu (with women respondents), Nyeri (with women respondents), and Nairobi (one with women respondents and another with men respondents). A total of 50 respondents (41 women and 9 men) from six political parties took part in the focus groups. Those in the focus group included those who vied successfully and unsuccessfully for various positions including Governor, Member of Parliament and Members of the County Assembly. The women in the focus group reported having been subjected to various forms of violence including physical, psychological, threats and coercion and economic violence. The acts of violence targeted both the women candidates and their families and they were perpetrated by opponents (both male and female) either directly or through the use of hired goons, as well as, some members of the security forces. These attacks were done to discourage, intimidate and ultimately prevent the women from participating in the elections. The male respondents also claimed to have faced violence from their opponents but agree that the women had it worse than them.

Participants in the focus group also highlighted how most of the violence against women as candidates occurred primarily before election day. For example, participants shared how psychological and verbal abuse was highly present. In one case in Nyeri, the aspirant’s mother was abused and her customers scared away from her business premises. In this case, the objective was to get the aspirant step down from the race to protect her family from the consequences of her candidature. Participants also highlighted emotional violence where family members or opponents used matters close to the women’s heart to discourage them from running. In one case, a respondent was accused of murdering her husband and using his money to seek election.

Participants in the focus groups felt that a lot of work still needed to go into civic education with the aim of promoting leadership by women. Participants felt that the patriarchal nature of our society appeared to be more pronounced during elections and specifically with regard to women’s leadership. They attributed this to the perceived ‘combative’ nature of some women candidates and women leaders.

Other countries

The Votes Without Violence project, initially developed by the National Democratic Institute, has examined violence against women in elections in the following countries. You can view each country's data individually or check out our cross-country analysis.

Burma

Cote D'Ivoire

Contested claims of victory during Côte d’Ivoire’s 2010 presidential election—the first in a decade—triggered widespread post-election violence, in which women were often the first victims.