Timor-Leste’s July 2017 parliamentary elections, and its earlier presidential polls in March, marked significant milestones for this island nation’s young democracy. The 2017 National Parliamentary Elections in Timor Leste were the first in which Timorese born after the country’s 1999 independence referendum were eligible to vote, helping to usher into parliament a new youth-based party - for the first time.

During Timor Leste’s 2017 national parliamentary elections, the Technical Secretariat for Electoral Administration (STAE), a government body that is within the Ministry of State Administration and Territorial Management, implemented all electoral activities. These included drafting of electoral regulations; compilation and management of the voter register; voter education; the procurement of electoral supplies and equipment; the administration of voting and counting of ballots; and the conduct of out-of-country voting. STAE had announced prior to the election day polls that they would seek gender balance among the polling officials. CET-OIPAS, a citizen election observer coalition, decided to monitor this proposal in its observation as one of its observation areas. While CET-OIPAS’ observation efforts included questions on women’s participation in the election, they were unable to incorporate VAW-E related questions. NDI provided technical and financial assistance to CET-OIPAS in order to strengthen its ability to conduct nonpartisan election observation and accurately and impartially assess the 2017 parliamentary and presidential election processes. CET-OIPAS was receptive to NDI input on gender inclusivity by incorporating gender-related questions in observer checklists for the parliamentary election. NDI is very grateful for its partnership with CET-OIPAS. At the time of publishing this report, final comments from CET-OIPAS had not been received. The report will be updated when they are.

According to the Asia Foundation’s report on, "Understanding Violence Against Women and Children in Timor Leste," due to Timor-Leste’s recent turbulent history, the normalization of violence is a part of the society’s daily life: violence is considered an accepted or justifiable form of conflict resolution. It is a perception extended to the use of violence against women. Domestic violence and sexual assault are not considered crimes by most communities, but rather a reality of everyday life. Domestic violence is a barrier to women’s political participation, as it involves the control of an individual’s movement, and a limitation on freedom of thought and expression. With 59 percent of women reporting that they have experienced domestic or sexual violence and with no community recourse to address these crimes, Timorese women’s ability to participate equally and actively in politics and the public decision-making that affects their lives is diminished.

BEFORE THE ELECTION

During the pre-election period, CET-OIPAS observers monitored the electoral environment which included campaigns. CET-OIPAS observed 195 rallies and 16 dialogues and meetings, none of which featured women speakers.

TIMOR LESTE: How Many OIPAS Observers Were There During The 30 Day Campaign Period?

ELECTION DAY

On election day, STAE staffed each voting center with a Presiding Officer, and 10 staff to every polling station. They included: one Secretary, two Queue Controllers, four Identification Verifiers, one Ballot Paper Controller, one Ballot Box Controller and One Ink Application Controller. STAE issued 17,443 accreditation cards for all the 21 contesting parties, of which 16,974 accreditation cards were for polling station party agents. STAE did not record gender on the accreditation cards that they issued to the parties and observers. As a result, we do not know the official number of how many women actually participated as polling station party agents.

CET-OIPAS deployed 841 observers, 278 or 33 percent of whom were women. The questions below were the first time that CET-OIPAS sought gender-disaggregated data in its observation. As part of pre-election support, a member of NDI’s Gender, Women and Democracy team met with CET-OIPAS and discussed the importance of gathering gender-disaggregated data during their observation effort. As an outcome of the meeting, CET-OIPAS incorporated gender disaggregated questions. Although these questions were not VAW-E specific, the data acts as a baseline for future observation efforts.

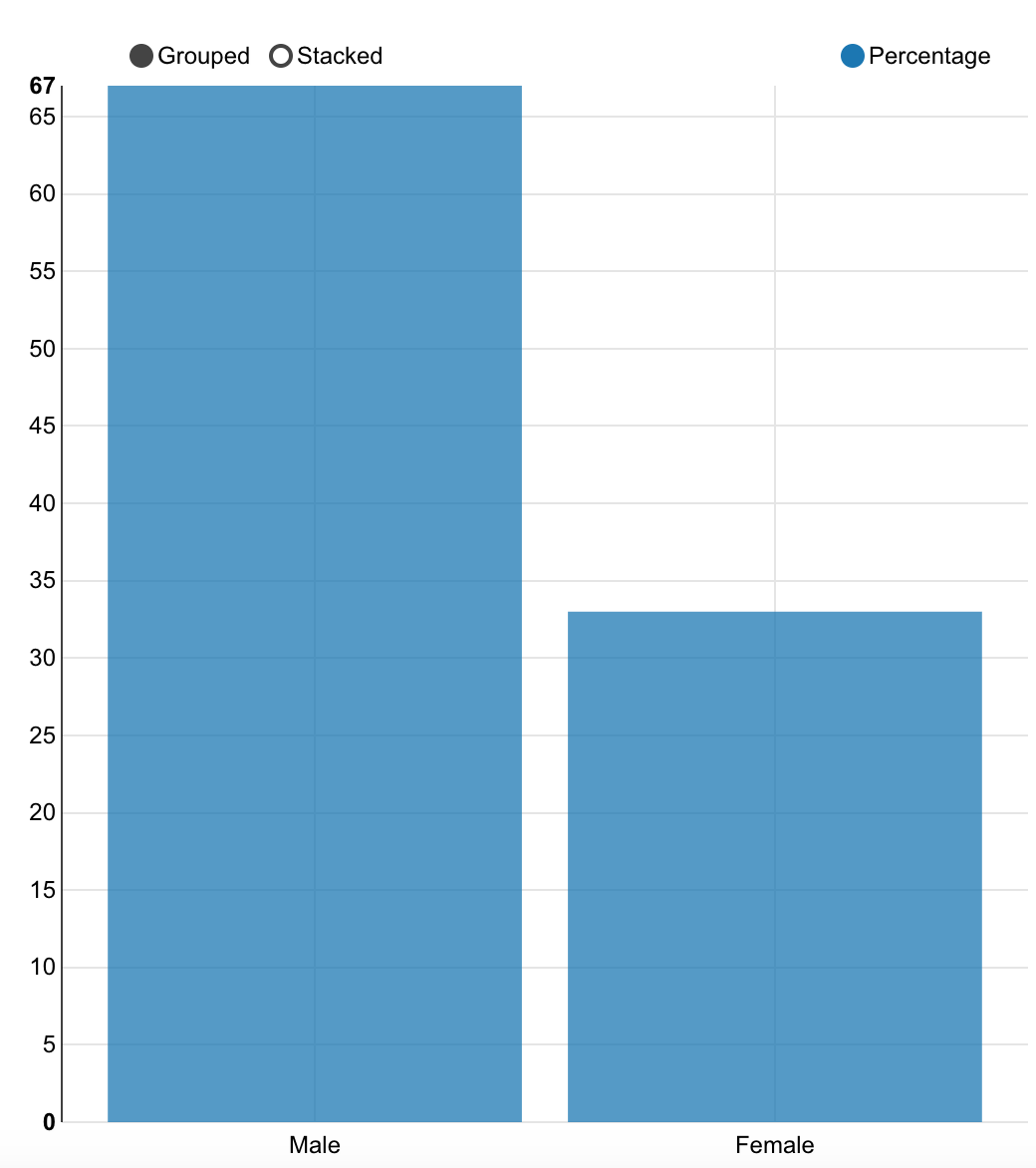

TIMOR LESTE: What Was The Percentage Of Election Day Observers?

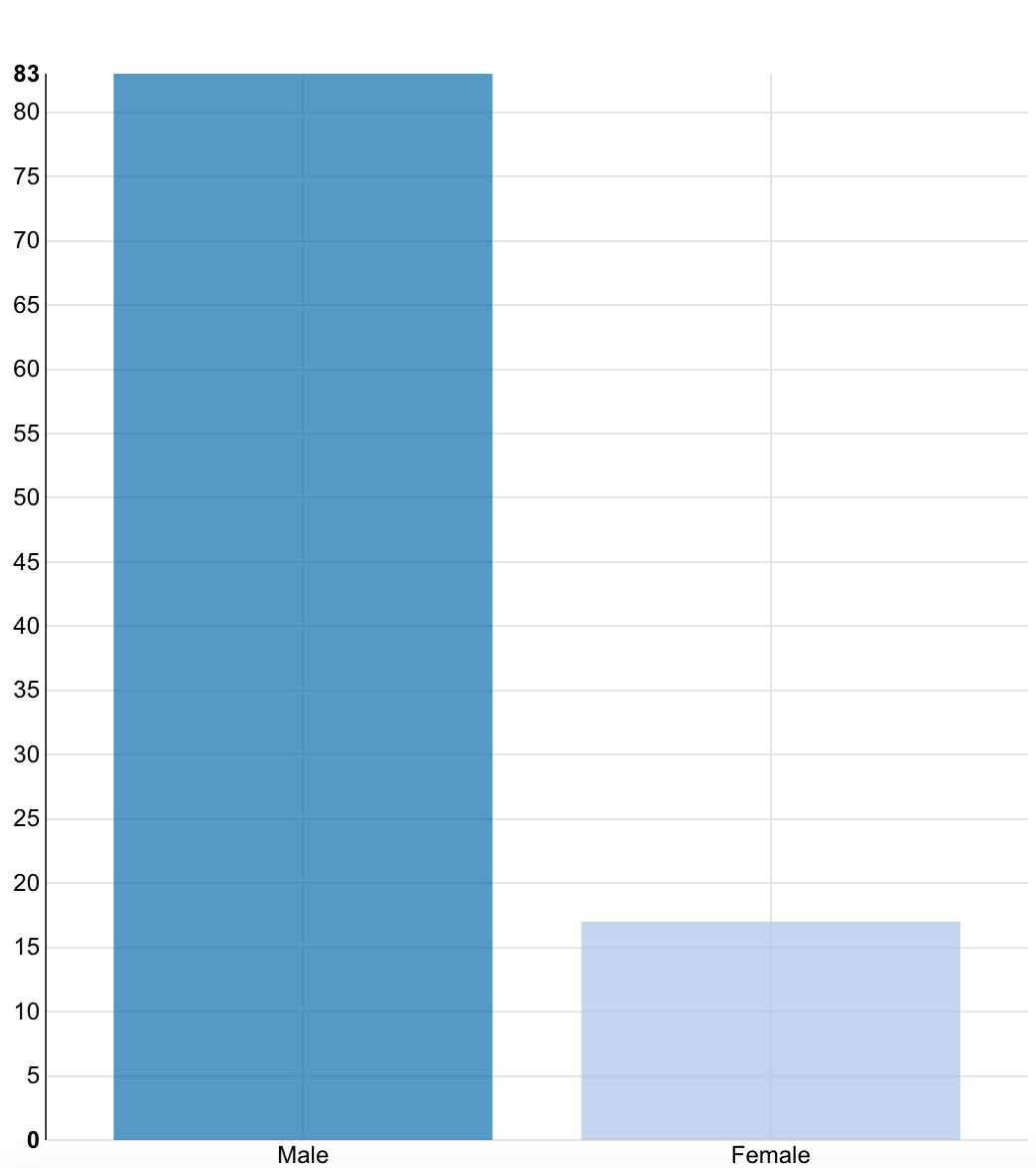

Timor Leste: What Was the Percentage of Polling Agents?

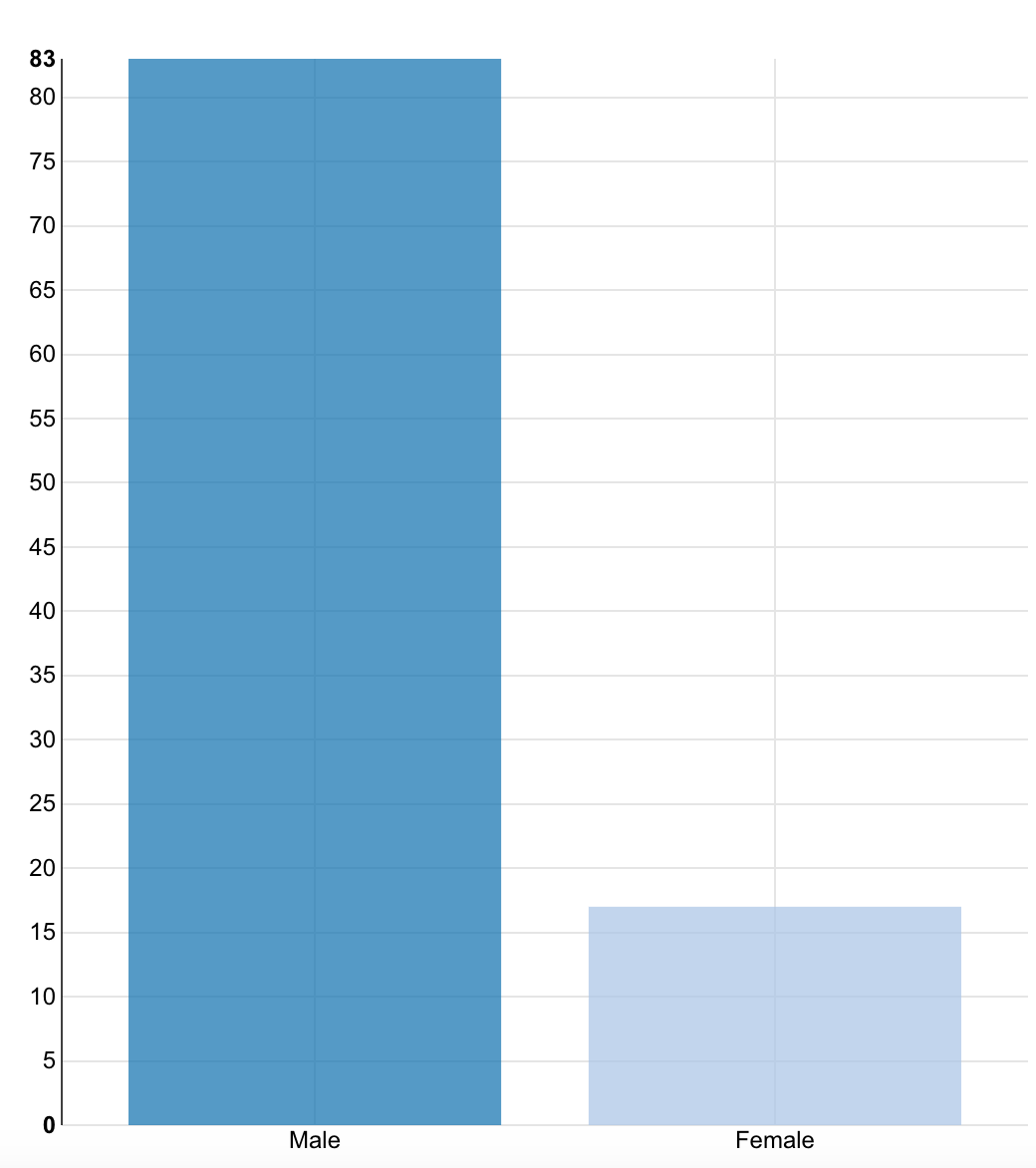

TIMOR LESTE: What Was The Percentage Of Polling Officials?

VAW-E IN TIMOR LESTE

Violence against women in politics (VAW-P) broadly, and violence against women in elections (VAW-E) in particular, are a significant barrier to women’s political participation in Timor-Leste. A 2016 study by the Asia Foundation found that three in five (59 percent) ever-partnered women aged between 15 and 49 years had experienced physical or sexual violence by a male partner in their lifetime, and almost one in two (47 percent) had experienced such violence in the previous 12 months. This violence is happening, and it does not disappear when women enter into politics or at election time. If close to half of women have experienced intimate partner violence in the past year, we can be almost certain that women involved in politics have experienced it as well.

As mentioned earlier, there is also a high degree of normalization of all forms of violence in Timor-Leste, and a limited awareness about VAW-E - in particular with regard to which actions constitute violence. Based on NDI’s qualitative analysis, the most common types of VAW-E reported in Timor-Leste were psychological violence, and domestic violence that manifests as physical violence, as well as threats and coercion. These tend to be less commonly recognized as violence and/or are difficult to observe directly by others.

Psychological violence:

The prevalence of psychological violence in Timor Leste is heavily tied to and drawn from the roles that men and women play in society. These traditional roles often restrict women’s freedom of movement to be able to go to political events and these roles often to do allow for women to lead on decisions that impact the community and/or larger society. For example, according to women’s groups and women candidates NDI spoke to, the arguments against women candidates often cite perceptions of women’s primary roles as a reason to not vote for women; e.g.: “She is a woman, so she will constantly be busy with her domestic duties, so how would she be able to be effective in her position?” and “How will a woman be able to travel to the different villages to be able to effectively represent the constituents? She won’t be able to travel and thus can’t represent us.” Women candidates also reported harassment at local level campaign events, where young men would shout and use harassing language while women candidates were trying to speak.

Domestic violence: Physical violence and threats and coercion:

Many examples of VAW-E were directly related to domestic violence, and manifested in the forms of physical violence, as well as threats and coercion. As described above, rates of domestic violence in Timor Leste are high. Physical domestic violence impacts women’s participation in elections in a variety of roles, including when they are acting as candidates and voters. In some cases, women feared participating as candidates or as party activists because they may face reprisals from their husbands in the form of physical violence, especially if their participation in politics led to them returning home at night. In other cases, the very presence of domestic violence in the home created an atmosphere of fear and coercion, wherein the women experiencing such violence would fear participating in politics or voicing their political opinions, regardless of whether the violence seemed to be directly aimed at electoral issues. For these reasons, many women NDI spoke with described a high prevalence of vote coercion in Timor Leste, accompanied by a general lack of awareness that such coercion in a violation of voting rights. This reality is perhaps best exemplified by a statement that NDI heard on more than one occasion: “Women will automatically vote with their husbands.”

Other countries

The Votes Without Violence project, initially developed by the National Democratic Institute, has examined violence against women in elections in the following countries. You can view each country's data individually or check out our cross-country analysis.

Burma

Cote D'Ivoire

Contested claims of victory during Côte d’Ivoire’s 2010 presidential election—the first in a decade—triggered widespread post-election violence, in which women were often the first victims.